Insightful Parenting

In this final article in the five part Insights on Discipline series, I explore some of the ways children can build a sense of responsibility and self-discipline from experiencing the natural consequences of behavioral choices they’ve made.

Experiencing the results of behaviors is another way to learn

For the most part, the articles in this series encourage you to guide your child toward success by supporting and cultivating behavior -- doing things like stating expectations in advance, role playing, taking advantage of teachable moments, or coaching in various ways. However, we also need to help our children learn how . . .

What Is "Positive Parenting"???

“Positive Parenting” is a widely embraced approach to child rearing, sometimes also called positive discipline, that focuses on trying to understand the reasons children behave as they do and guiding them in ways that are positive and kind rather than punitive. If you enter the term in your search engine you will find a lot of websites, based in many English speaking countries, that offer various takes on positive parenting. You’ll also find several attempts to define it, some tracing its roots to a rebellion against behaviorism. Others trace its roots to

Offering guidance to children in advance of events is a way of preparing children to be skillful. It is setting them up to be successful rather than to struggle with incompetence and a lack of information. On first reading, you may think I mean that parents should design situations where their child is bound to excel, creating perfect scenarios where kids hit bullseyes when they throw balls, get every answer right on an easy game of trivia, or add the final piece to a nearly complete puzzle. Definitely not!! That simply undermines children’s drive to try for themselves and . . .

A little background

Behaviorism held sway throughout the first six decades of the 20th century. It’s based on the idea that human and animal behavior can be explained and taught by training, or conditioning, through a system of rewards and reinforcements. It does not consider emotions, feelings, individual skills, or personal volition. The big names in the field of behaviorism may be familiar: John Watson, Ivan Pavlov and B. F. Skinner. Watson once famously boasted that he could train any human child to become anything – a pianist, a writer, a surgeon – through training and reinforcement. Seems pretty laughable now, since of course that isn’t possible nor, hopefully, would we want to attempt it. Behaviorism was challenged from many sides, especially in the 1960s and early 1970s by psychologists and linguists. It was also very much at odds with humanistic psychology, which stressed that a person’s subjective experiences were paramount (as in the work of Carl Rogers and Rollo May).

The basic tenets of behaviorism, particularly the use of rewards and reinforcement, are key to animal training and are used today to teach service animals, companion animals, and animals used in law enforcement.

These techniques are justifiably debunked for “training” (yikes!) children. Techniques of behaviorism can train kids to act appropriately in some situations, but they certainly don’t build self-regulation, self-confidence, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, nor many other things we value and recognize as part of our basic humanity. Never-the-less, there are actually some surprising lessons we can learn from behaviorism. What I’m going to discuss gets at the underlying ways we respond to certain experiences, not how to use a contrived system of rewards and punishments.

So, here’s what we can learn and use from behaviorism. The insights may surprise you!!

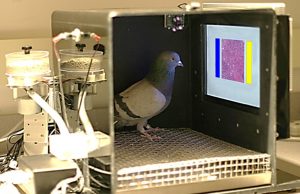

How to train a pigeon to peck at a light panel

Legions of psych students did this in the mid 20thC. The goal is to train the pigeon to peck at the little light panel on one side of the box. Notice that outside the box is a device that can deliver sunflower seeds (much loved by pigeons) to a little feeding dish in the box.

You may think that the way to train is to deliver some sunflower seeds when the pigeon happens to peck at the light, with the idea that the pigeon will soon associate pecking the light with a nice reward and will therefore enjoy pecking at the light. But it isn’t quite that simple! It might work, but it would take a long time, probably more than the class semester. Chances are the pigeon wouldn’t peck much at the light if just left to do its thing and sometimes get seeds.

Here’s what the psych students had to do:

Step 1. Break down the desired behavior.

The pigeon will be: Pecking. Pecking in a particular location. Pecking on a particular object (the light panel)

Step 2. Determine the reward. In this case seeds. It helps if the pigeon is a little hungry when a session begins, so you don’t work with your pigeon right after it’s been fed a meal.

Notice now “you” (the psych student) have two things in mind: you’ve broken down the behavior and you have a provided a motivation for pecking.

Step 3. Start by rewarding the basic behavior! Give your pigeon a seed every time it pecks. Pigeons randomly do various things: they peck, preen, coo, prance around, fluff their feathers. You’re only giving seeds when it pecks. Guess what? The pigeon quickly associates pecking with sunflower seeds and happily pecks more and more.

Step 4. Now you get a bit more specific. You gradually tighten up the criteria for giving the reward. Perhaps your pigeon only gets a seed when she pecks while facing toward the wall with the light panel on it, then maybe only when she’s actually pecking that wall, and eventually only when she pecks the light panel itself.

⇒ That is called shaping.

Do we “shape” Kids??

You’ve already done this kind of thing as a parent, probably quite instinctively. Here’s a great example. Think back to when your infant was small. She turned toward your face and you greeted her with a warm smile and a little comment, probably a sweet high pitched sing-song baby talk greeting, like “Hi there little one. Hi.” (And yes, baby talk is fine. Great even. We do it because babies respond to it.) You keep gazing, waiting for your tiny one to smile at you or burble. And of course she does. So you comment on that, “Are you smiling? What a nice smile.” Or maybe even, “Oh, oh, is that a little burp? Huh? Did you burp?”

You’ve already done this kind of thing as a parent, probably quite instinctively. Here’s a great example. Think back to when your infant was small. She turned toward your face and you greeted her with a warm smile and a little comment, probably a sweet high pitched sing-song baby talk greeting, like “Hi there little one. Hi.” (And yes, baby talk is fine. Great even. We do it because babies respond to it.) You keep gazing, waiting for your tiny one to smile at you or burble. And of course she does. So you comment on that, “Are you smiling? What a nice smile.” Or maybe even, “Oh, oh, is that a little burp? Huh? Did you burp?”

Over time, you and your infant engage more and more in these little interactive envelopes the two of you share. As the months unfold, your infant becomes more and more skilled in her role: she babbles language sounds, points, sings tunes with you and eventually says a few little words. As your baby built these interactive skills, you were gradually changing how you responded: you didn’t treat a burp as if it were a turn in a conversation once your baby began to babble a bit, and so on. Notice that what you were doing over these months was gradually guiding your baby to become a skilled interactor. You were teaching your little one to take turns with you, to take part in two-way conversations. You were shaping a really important human skill! While you and your infant really enjoyed these wonderful exchanges, and they helped create a nice bond between you, you were also shaping your infant’s behavior! You were “rewarding” her with your loving attention and opportunities to interact with you, and gradually showing her that we humans take turns and we mostly we use language and focus of attention in those interactions.

Is it really just “shaping” with children??

With little infants, it often does seem very much like shaping (though to be fair, infants also have many innate or quickly developing skills they use on their own). As children grow, it is really much more. When you break down a task and guide your child to build skills, you are scaffolding development. Your child will feel a sense of accomplishment as each step is mastered. So among other things, you are nurturing your child’s sense of confidence and self-esteem. She or he will also feel respected, because you are making it possible for your child to assume more and more responsibility for a task. We humans are self-reflective and have complex cognitive and emotional responses. Returning to the example of how you taught your infant to take turns in a conversation, we can see some clear emotional development as well. You showed your infant how to interact with you, but you also taught her somethings about language and you nurtured a deep affectionate bond. As far as we know, pigeons don’t have these kinds of thoughts and emotions. So supporting children’s development in this way draws on strategies used to shape behavior in training animals, but we are not simply training someone to mindlessly do something.

Back to Pigeons

Within a few days you have a pigeon happily pecking away at the light panel.

Stopping (Extinguishing) The Behavior

Now let’s say you’d like your pigeon to STOP this behavior, that is, you’d like your pigeon to NOT keep pecking at the light panel. What should you do?

It’s pretty easy. Stop giving the pigeon sunflower seeds when it pecks at the light. For a while your pigeon will keep pecking. But eventually she’ll sort of give up. She’ll begin to peck other places in the box, only occasionally pecking the light panel. You will have “extinguished” the behavior. No reward, no behavior. Hang on to this idea, because I’ll return to it. But first let’s consider how to maintain the pecking behavior.

How To Maintain The Behavior

Suppose instead, you decide you want your pigeon to continue to peck at the light panel, to keep up this behavior you’ve trained her to do. What should you do?

You might think a good plan is to keep giving your pigeon a reward. But guess what? That is actually not a good plan!! If you reward your pigeon every time she pecks, she will continue to peck. But she’ll do other things too. She’ll peck other places and she’ll prance more and preen more and fluff her feathers more.

Be Inconsistent!

If you want to keep your pigeon pecking that light panel fairly often, you reward her some of the time and other times you don’t reward her at all. You need to become inconsistent!!! In psych labs this is called, “variable schedule reinforcement.” What it means is that you deliver sunflower seeds at random times, typically following a randomly generated schedule that neither you nor your pigeon know in advance. You just dutifully deliver a sunflower seed whenever a printed schedule tells you to do so. Peck seed, peck seed, peck no seed, peck no seed, peck no seed, peck seed, peck no seed. You get the idea. Your pigeon will get totally engaged with pecking and she’ll peck that light panel much more than she does other things. (I thought of saying she’s obsessed with pecking, but I don’t want to imply any psychosis!! She just enjoys it and is motivated to peck. She’ll likely stop for a while if she’s too full for example.)

Inconsistency is an incredibly powerful reward!

It works with training animals, but inconsistency is astoundingly powerful for us too! We humans get hooked by inconsistency.

Think back to your dating days. Maybe you got involved with a charming person (or maybe it happened to someone you know.) This person took you out, you had fun together, told you how amazing you were, called the next day to tell you what a fun evening it was and that s/he wants to get together again soon. The person promises to call soon. You were excited and waited for the call. No call. No call. No call. CALL! You get the idea. You (or someone you know who experienced this) got hooked in part by the random reinforcement. There were nice rewards (compliments, fun times together). Nice rewards, but you had no idea when they were coming, and that made them very potent. Dare I say you (or that friend of yours) got obsessed? That’s the power of inconsistency!

♥ Like you, like all of us, (even like pigeons), your child will respond to inconsistency. The key is to know how to use it wisely!!

This is a very, very powerful insight. You can use inconsistency in some very skillful and powerful ways to help your child build skills, but it can also undermine you. You need to use it thoughtfully and knowingly.

Inconsistency Used Wisely

♥ When your child has learned to do something skillfully that you would like him to maintain, you might want to encourage it by being inconsistent.

Notice and comment on the skillful behavior SOME OF THE TIME

High five good stuff SOME OF THE TIME

Tell your child you noticed he did X or Y the other day SOME OF THE TIME

Offer a reward for responsible or desirable behavior SOME OF THE TIME

Why?

- Randomness is a powerful reinforcer

- Ultimately, you want your child’s own sense of accomplishment to help him or her self-monitor and self-control behavior. You don’t want to have the desire for a reward to become the motivation.

♥ Rewards are actually a kind of scaffold. We sometimes use them to support our child as they learn. But like any scaffold, the real goal is to remove the scaffold and let the building — or the child — stand alone.

What’s a good reward??

Don’t use sweet treats and other kinds of food. (Kids think more than pigeons!) You want your child to have a healthy relationship with food, not associate it with rewards or punishments. Great rewards are things like special time with a parent doing something you both enjoy, getting to pick a place to go for an outing (yes, including picking a restaurant — that’s different from offering a food reward), getting some new books from the library, being given a new privilege, having a friend over. You get the idea. Rewards should offer positives (getting to play with water balloons) and not removal of something the child thinks of as negative (you don’t have to clean your room, or you don’t have to practice the piano today). Toward the end of this article you’ll find more ideas for rewards.

Be aware of how inconsistency can undermine parenting efforts

Is this familiar? We’ve all done this: You don’t want your child to stream a show for more than 30 minutes. Or to watch it without you. And you don’t want her to eat sweets before dinner and while watching the show. You’re pretty good about reminding your child about this and monitoring her activity.

Then one day you have a bad day. One of those very bad terrible awful days. You’re totally stressed. You just want down time. Of course this is the day your child fusses for super sweet snacks, refusing an apple and cheese, and begs to use an iPad for an extra-long time. (Children are brilliant at picking up signs that we’re stressed). So, for the sake of some peace, you give her the snack she wanted and leave her with the iPad for over an hour. Guess what you’ve just reinforced? You’ve shown her that begging and fussing gets results.

There’s no way this won’t happen. But I think it’s really helpful to understand the effect and be able to reflect on it. It may help you react differently some of the time or perhaps get help from your partner or a friend.

Can you fix that kind of mistake?? Yes! Talk about it with your child later.

“You know, I gave you chocolate cookies today and let you use the iPad for a long time. Those weren’t good things for me to do. I had a difficult day at work and felt really tired and stressed. I’m sorry. Can you help me remember we shouldn’t have sweets before dinner? Or spend a long time on the iPad? And can I have hug; I could really use one.”

♥ Being able to discuss and share is one of the big differences between “training an animal” and guiding a child.

♥ Doing so is honest and informative behavior on your part.

♥ It communicates to your child that you respect him. And trust him. You’re treating your child as a responsible person when you share this information.

♥ It acknowledges your own less-than-perfect behavior – demonstrating to your child that people make mistakes, and that acknowledging them is a good thing. It teaches responsibility. It even encourages empathy (pointing out how you felt).

The take away is to be aware that inconsistency can undermine your efforts to guide your child when it  used to unwittingly reinforce undesirable behavior. It can work like a boomerang, coming back to you. Certainly, this should encourage you to be mindful of times when something you do is inconsistent with your goals for helping your child build skills.

used to unwittingly reinforce undesirable behavior. It can work like a boomerang, coming back to you. Certainly, this should encourage you to be mindful of times when something you do is inconsistent with your goals for helping your child build skills.

Try to think twice before changing or “giving in.” On the other hand, you are human and have challenges too. Your less skillful choices don’t define you and they won’t totally undo skills you are trying to help your child establish. Children aren’t Pigeons: they have deeper thoughts and reflect on their emotions in ways pigeons don’t seem to. As a result, you can talk to your child about what happened, teaching some very good lessons and role modeling integrity, honesty and openness.

Extinguishing behavior

Recall that when a psych student wants to get a pigeon to stop pecking the light panel, the student stops offering a reward for pecking. If you would like a behavior to end, you might try to not reward it. No reward is how you extinguish (end, eliminate) a behavior.

You may want to reflect on what this means. When you pay attention to an undesirable behavior by noticing it and making a big deal about it, or when you make exceptions to rules, you are at some level rewarding it. It may seem counterintuitive. Some children (probably all on occasion) will do something they know is wrong in order to get attention or to divert attention from something even worse. If it’s safe and reasonable to do so, you may want to ignore the behavior: just walk away, don’t engage.

Trust your intuition to guide you on this; sense when your child is wanting your attention or perhaps “testing” you. (♥ If your child wants your attention, please note this in your heart and come back in a short while, when the silly behavior has ended, to connect and interact with your child.) Obviously you shouldn’t ignore dangerous, disturbing stuff. When you need to step in, do so in as simple and quick a way as possible; don’t discuss it. As soon as you can, give your attention to something else.

Oh, and just for the record, ignoring that your child is playing videos or games on a screen sure isn’t going to extinguish it!

Using Rewards

There are two broad types or rewards: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic rewards are ones we create and offer to encourage behavior. The human equivalent of sunflower seeds. Intrinsic rewards are even more potent: they are internal. The feelings of accomplishment, mastery, pride, confidence, and self-esteem that come from gaining skills are powerful intrinsic rewards.

You may occasionally want to use extrinsic rewards, things your child can “earn.”

It’s best not to do this for everything. Save these for something important where you feel it will help your child. It’s fine, in fact good, to let your child know that she or he will earn something special or is working toward a goal. You may want to ask your child to suggest some things to earn.

These kinds of rewards can be motivating, but should not become your basic mode of discipline. Relying on them sets up a relationship where your child expects to be “paid” for being “good.” It trains a behavior, but does little to build self-discipline, which is the real goal of guiding behavior in the first place. Save earning stickers and prizes for occasional times when you want to build good habits.

Here are examples of extrinsic rewards:

Crossing off days on a calendar. No other reward is offered — it’s amazingly satisfying to see a visible record of one’s successes. Many children feel empowered by this simple record of achievement. You might use this for recurrent things like practicing piano, studying spelling words for 15 minutes, having their school backpack filled and waiting by the door.

Stickers. A bit like the calendar, child places the stickers on calendar OR let your child actually earn stickers or trading cards or little items, whatever is currently “in.” Try putting them in a glass jar to be admired as they accumulate and opened at the end of the week.

Earning/working for something specific. This is often a good choice during middle childhood. Your child may like having a sleepover, getting a new book, going to the park/climbing wall/other special place. Choose things together that your child would like to have or do.

There is another form of extrinsic reward that is very powerful. These aren’t activities or material things, but they are external because they are offered by you rather than emerging from within the child.

Acknowledgement: It lets your child know you noticed. Children feel validated, appreciated, respected. Examples: I saw you put your apple core in the compost bin without anyone reminding you; You studied your spelling words all by yourself to day; You did a great job cleaning your room. Or a give a playful high-five.

Thanking: Similar to acknowledgement, but introduces gratitude. Feeling grateful is a very positive emotion. When you express gratitude, you are role modeling graciousness and inviting your child to experience gratitude in his life too. Examples: Thanks for putting your clothes in the hamper; thanks for watching your little brother while I was on the phone.

Informative comments: These are another form of acknowledgement, but here you are also teaching. By pointing out the beneficial consequences of the child’s skillful behavior your reinforcing AND helping your child gain a better understanding of things. Example: “You made Jake feel a lot better when you hugged him, he was feeling really sad when he got hurt.” In this example case, your comment promotes empathy by pointing out how another person feels (the hurt child), making it very conscious for your child.

Intrinsic rewards have enormous value

For us humans, many rewards are intrinsic, they come from the individual’s mindful attention to his or her own efforts. Our children create these for themselves. Children set their own goals and feel internal joy at learning to count, reading books, driving a car, getting into college. They also feel joy when they behave skillfully.

Ultimately, you want to withdraw the scaffold of rewarding and acknowledging successful behavior as your child gains self-competence. This builds self-efficacy, which is when one’s own actions lead to outcomes. Let your child take control as soon as she or he can. This shift of responsibility is one of the important ways guiding children is very different from merely shaping/training the behavior of animals.

Shifting responsibility to your child does not extinguish a behavior, because you make this shift once the child has gained a skill or behavior and is using it on his or her own initiative.

Key Insights From Behaviorism

♥ When you want to help your child build a skill or learn conventions for doing things, start by thinking about the behavior and breaking it down into component or simpler steps.

♥ Skills and behaviors can often be nurtured through a kind of shaping, in which successive approximations of the desired behavior are acknowledged or rewarded.

♥ You may occasionally want to use extrinsic rewards. Things children can “earn,” to encourage them to work on a skill. These can be motivating, but should mainly be used to help your child build good habits. Please don’t rely on them.

♥ Remember that undesirable behaviors can often be “extinguished” (ended) if they are not rewarded.

♥ Be Consistent when you are helping your child build skills or learn effective behaviors. Don’t make exceptions to family rules and don’t give mixed messages about expectations.

♥ Be Inconsistent once your child has learned a skill or behavior and you’d like it to persist. At this point, acknowledgements or rewards are best given at inconsistent and unpredictable times.

♥ Beware that inconsistent behavior on your part may “accidentally” encourage poor behavior.

♥ Ultimately, you want to withdraw the scaffold of rewarding and acknowledging success as your child gains self-competence.

What "discipline" means

It’s pretty easy to equate “discipline” with punishment, or trying to stop poor behavior, but as you probably know, discipline does not mean punishment. It’s really important to remember that as parents.

We sometimes hear that military leaders strive to “maintain discipline.” That suggests controlling people with punishment or with nasty consequences administered to offenders. What needs to be “maintained” is appropriate conduct or behavior.

The word discipline can also refer to teaching people rules about how to behave in particular situations. In this sense, “discipline” suggests something about teaching or guiding, rather than punishing . . .

It’s totally natural to get excited about our children’s accomplishments and successes. We feel proud and we want to share their joy. It feels great when our child scores a winning goal, aces a test, makes varsity, has artwork displayed, plays a solo in orchestra, or stays balanced on a bike. What’s not to like? At the same time, you’ve probably read parenting advice that tells you not to praise too much. You’ve probably also read that it’s important to . . .

These six strategies nurture your child and yourself and strengthen the close trusting bonds between you. If you decide to use them, you’ll find you and your child are calmer, happier, more connected. Plus, you’ll also be amazed at how much more responsibly your child will behave!!!

Each of the tips is based on developmental science research, positive psychology, and clinical practice.Try incorporating them into your daily life, and see what happens. Don’t worry at all if you don't do them perfectly or you forget them sometimes. Be kind to yourself, and when . . .

When your child (or you!) needs to de-stress and restore, getting out into nature has a quick and astounding impact.

Classrooms, work and urban environments require us to focus attention and block out distractions. It’s mentally exhausting and causes physical and mental fatigue in children and adults. Being in nature has the opposite effect. It encourages a kind of open, less focused attention called, “undirected attention.” We experience that as pleasurable, positive and calming. Nature restores fatigued brains. Just a small dose, a pause for a few minutes outdoors disconnected from cell phones or other technology resets our . . .

The comments and experiences children get, both the positive and the negative, can reverberate throughout life.

A kind comment feels good and it may draw a child’s attention to one of their gifts or help them confirm a feeling they’ve had about their special skills. Imagine how a child feels hearing something like these comments: “This is a beautiful picture,” “You were such a fast runner today,” “That was a great idea,” “You made your friends feel so comfortable at the party this afternoon.” As you read these kinds of comments you may even feel yourself relax and . . .